Asymmetric Risks of Momentum Strategies is another attempt to explain the excess returns of momentum using the Capital Asset Pricing Model. The paper discusses a theory of risk asymmetry in momentum risk/reward, but not how to gain an edge from it.

Abstract:

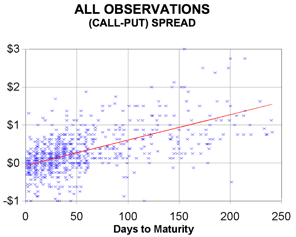

I provide a novel risk-based explanation for the profitability of global momentum strategies. I show that the performance of past winners and losers is asymmetric in states of the global market upturns and downturns. Winners have higher downside market betas and lower upside market betas than losers, and hence their risks are more asymmetric. The winner-minus-loser (WML) momentum portfolios are subject to the downside market risk, but serve as a hedge against the upside market risk. The high return of the WML portfolios is a compensation for their high risk asymmetry. After controlling for this risk asymmetry, the momentum portfolios do not yield significant abnormal returns, and the momentum factor becomes insignificant in the cross-section. The two-beta CAPM with downside risk explains the cross-section of returns to global momentum portfolios well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.