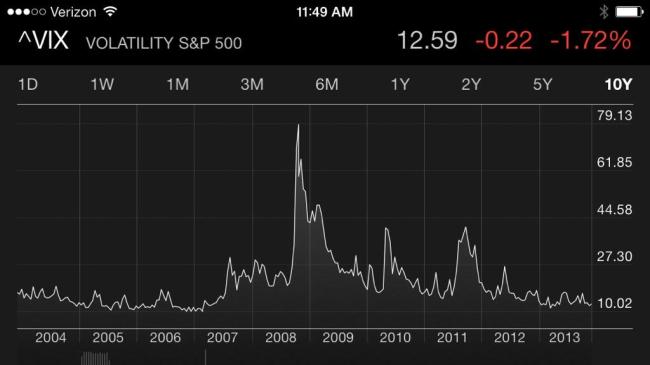

Implied volatility, the amount of “insurance premium” implied by the price of options, continues to suggest that investors are becoming very complacent. When the VIX is high or rising, it says the market expects the S&P to move up or down more. When the VIX is low or declining, it says the market expects the S&P 500 will not move up or down as much in the future. That is, the “insurance premium” priced into options on the S&P 500 stocks is low. That isn’t necessarily directional – it is an indication of the expected range, not necessarily direction. However, what I know about directional price trends is that after a price has been trending directionally for some time, as the S&P 500 stock index has, investors become more and more complacent as they expect that trend to continue. The mind naturally wants to extrapolate the recent past into the future and it keeps doing it until it changes. When we see that in the stock market, it usually occurs as a directional trend is peaking. Investors are caught off guard as they expected a tight range. If the range in prices widens, they probably widen even more because they are – and it wasn’t expected. Interestingly, people actually expect inertia and that is one of the very reasons momentum persists as it does. Yet, momentum may eventually move prices to a point (up or down) that it may move too far and actually reverse the other way.

If we believe the market is right, we would believe the current level accurately reflects the correct expecation for volatility the next 30 days. That is, we would expect today’s implied volatility of about 12 – 13% will match the actual historical volatility 30 days from now. In other words, 30 days from now the historical (backward looking) volatility is match the current implied volatility of 12.6%. If we believe the current volatility implied by option premiums is inaccurate, then we have a position trade opportunity. For example, we may believe that volatility gets to extremes, high or low, and then reverses. That belief may be based on empirical observation and quantitatively studying the historical data to determine that volatility is mean reverting – it may oscillate in a range but also swing from between one extreme to another. If we believe that volatility may reach extremes and then reverse, we may believe the market’s implied volatility is inaccurate at times and aim to exploit it through counter-trend systems. For example, in my world, volatility may oscillate in a range much of the time much like other markets, except it doesn’t necessarily have a bias up or down like stocks. There are times when I want to be short volatility (earning premium from selling insurance) and long volatility (paying premium to buy insurance). I may even do both at the same time, but across different time frames.

The point is, the market’s expectation about the future may be right most of the time and accurately reflect today what will be later. But, what if it’s wrong? If we identify periods when it may be more likely wrong, such as become too complacent, then it sets up a position opportunity to take advantage of an eventual reversal.

Of course, if you believe the market is always priced accurately, then you would never take an option position at all. You would instead believe that options are priced right and if you believe they are, you believe there is no advantage in being long or short them. I believe the market may have it right most of the time, but at points it doesn’t, so convergence trades applying complex trade structures with options to exploit the positive asymmetry between the probability and payoff offers the potential for an edge with positive expectation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.