I was talking to an investment analyst at an investment advisory firm about my ASYMMETRY® Global Tactical and he asked me what the standard deviation was for the portfolio. I thought I would share with you how the industry gets “asset allocation” and risk measurement and management wrong.

Most people have poor results over a full market cycle that includes both rising and falling price trends, like global bull and bear markets, recessions, and expansions. Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, SPIVA, Morningstar and many academic papers have provided empirical evidence that most investors (including professionals) have poor results over the long periods. For example, they may earn gains in rising conditions but lose their gains when prices decline. I believe one reason is they get too aggressive at peaks and then sell in panic after losses get too large, rather than properly predefine and manage risk.

You may consider, then, to have good results over a long period, I necessarily have to believe and do things very differently than most people.

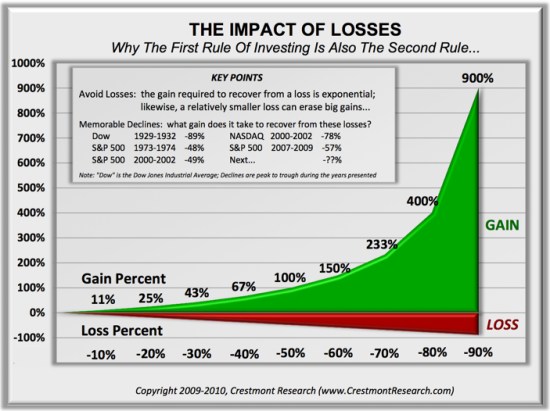

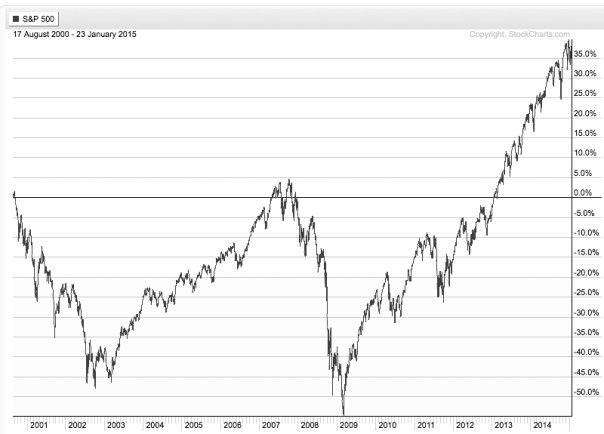

On the “risk measurement” topic, I will share with you a very important concept that is absolutely essential for truly actively controlling loss. The worst drawdown “is” the only risk metric that really matters. The risk is not the loss itself. Once we have a loss, it’s a loss. It’s beyond the realm of risk. Since risk is the possibility of a loss, how often it has happened in the past and the magnitude of the historical loss is the expectation. Beyond that, we must assume it could be even worse some day. For example, if the S&P 500 stock index price decline was -56% from 2007 to 2009, then we should expect -56% is the loss potential (or worse). When something has happened before, it suggests it is possible again, and we may have not yet observed the worst decline in the past that we will see in the future.

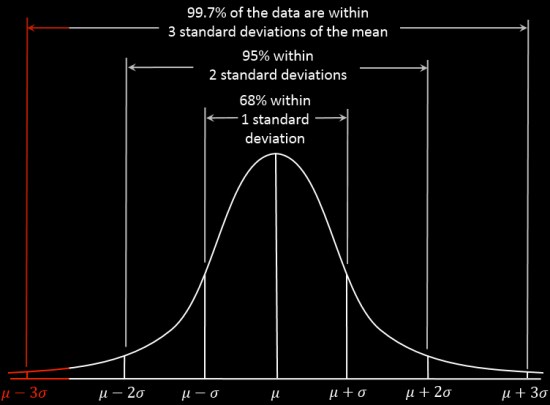

The use of standard deviation is one of the very serious flaws of investors attempting to measure, direct, and control risk. The problem with standard deviation is that the equation was intentionally created to simplify data. The way it is used draws a straight line through a group of data points, which necessarily ignores how far the data actually spreads out. That is, the standard deviation is intended to measure how far the data spreads out, but it actually fails to absolutely highlight the true high point and low point. Instead, it’s more of an average of those points. However, for risk management, it’s the worst-case loss that we really need to focus on. I believe in order to direct and control risk, I must focus on “how bad can it really get”. Not just “on average” how bad it can get. The risk in any investment position is at least how much it has declined in the past. And realizing it could be even worse some day. Standard deviation fails to reflect that in the way it is used.

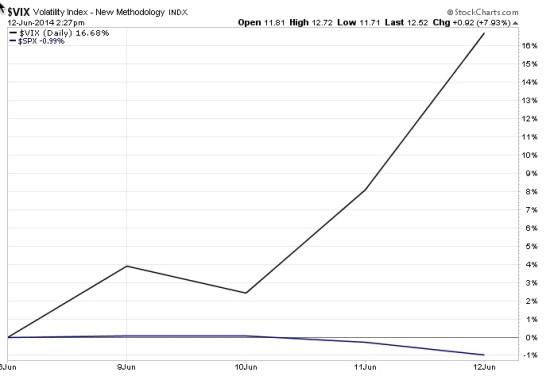

Consider that as prices trend up for years, investors become more and more complacent. As investors become complacent, they also become less indecisive as they believe the recent past upward trend will continue, making them feel more confident. On the other hand, when investors feel unsure about the future, their fear and indecisiveness is reflected as volatility as the price swings up and down more. We are always unsure about the future, but investors feel more confident the past will continue after trends have been rising and volatility gets lower and lower. That is what the peak of a market looks like. As it turns out, that’s just when asset allocation models like Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and portfolio risk measures like Value at Risk (VaR) tell them to invest more in that market – right as it reaches its peak. They invest more, complacently, because their allocation model and risk measures tell them to. An example of a period like this was October 2007 as global stock markets had been rising since 2003. At that peak, the standard deviation was low and the historical return was at its highest point, so their expected return was high and their expected risk (improperly measured as historical volatility) was low. Volatility reverses the other way at some point

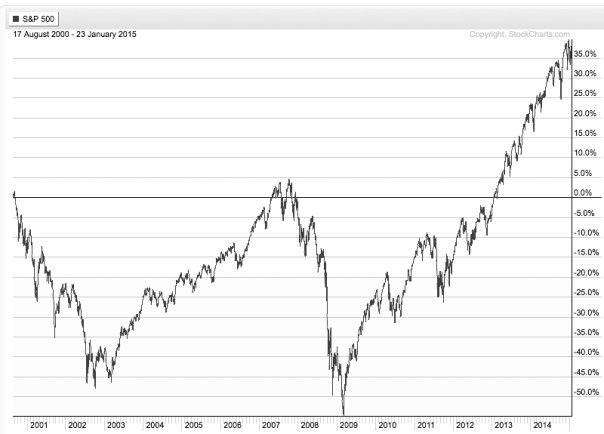

What happens next is that the market eventually peaks and then begins to decline. At the lowest point of the decline, like March 2009, the global stock markets had declined over -50%. My expertise is directional price trends and volatility so I can tell you from empirical observation that prices drift up slowly, but crash down quickly. The below chart of the S&P 500 is an example of this asymmetric risk.

At the lowest point after prices had fallen over -50%, in March 2009, the standard deviation was dramatically higher than it was in 2007 after prices had been drifting up. At the lowest point, volatility is very high and past return is very low, telling MPT and VaR to invest less in that asset. This is a form of volatility targeting: investing more at lower levels or historical volatility and less at higher levels.

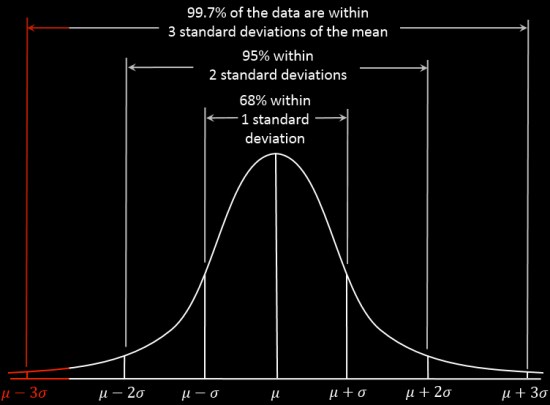

In the 2007 – 2009 decline in global markets, you may recall some advisors calling it a “6 sigma event”. That’s because the market index losses were much larger than predicted by a standard deviation. For example, if an advisors growth allocation had an average return of 10% in 2007 based on its past returns looking back from the peak and a standard deviation of 12% expected volatility, they only expected the portfolio would decline -26% (3 standard deviations) within a 99.7% confidence level – but the allocation actually lost -40 or -50%. Even if that advisor properly informed his or her client the allocation could decline -26% worse case and the client provided informed consent and acceptance of that risk, their loss was likely much greater than their risk tolerance. When they reach their risk tolerance, they “tap out”. Once they tap out, when do they ever get back in? do they feel better after it falls another -20%? or after it rises 20%? There is no good answer. I want to avoid that situation. I prefer to reduce my exposure to loss in well advance.

You can see in the chart below, 3 standard deviations is supposed to capture 99.7% of all of the data if the data is a normal distribution. The trouble is, market returns are not a normal distribution. Instead, stock market gains and losses present an asymmetrical return distribution. Market returns experience much larger gains and losses than expected from a normal distribution – the outliers are critical. However, those outliers don’t occur very often: historically it’s maybe every 4 or 5 years, so people have time to forget about the last one and become complacent.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/68%E2%80%9395%E2%80%9399.7_rule

My friends, this is where traditional asset allocation like Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and risk measures like Value at Risk (VaR) get it wrong.

These methods are the most widely believed and used . You can probably see why most investors do poorly and only a very few do well – an anomaly.

I can tell you that I measure risk by how much I can lose and I control my risk by predefining my absolute risk at the point of entry and my exit point evolves as the positions are held. That is an absolute price point, not some equation that intentionally ignores the outlier losses.

As the stock indexes have now been overall trending up for 5 years and 9 months, the trend is getting aged. In fact, according to my friend Ed Easterling at Crestmont Research, at around 27 times EPS the stock index seems to be in the range of overvalued. In his latest report, he says:

“The stock market surged over the past quarter, adding to gains during 2014 that far exceed underlying economic growth. As a result, normalized P/E increased to 27.2—well above the levels justified by low inflation and interest rates. The current status is approaching “significantly overvalued.”

At the same time, we shouldn’t be surprised to eventually see rising interest rates drive down bond values at some point. It seems from this starting point that simply allocating to stocks and bonds doesn’t have an attractive expected return.

I believe a different strategy is needed, especially form this point forward.

In ASYMMETRY® Global Tactical, I actively manage risk and shift between markets to find profitable directional price trends rather than just allocate to them.

Mike Shell is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Shell Capital Management, LLC, and the portfolio manager of ASYMMETRY® Global Tactical.

The observations shared on this website are for general information only and are not specific advice, research, or buy or sell recommendations for any individual. Investing involves risk including the potential loss of principal an investor must be willing to bear. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The presence of this website on the Internet shall in no direct or indirect way raise an implication that Shell Capital Management, LLC is offering to sell or soliciting to sell advisory services to residents of any state in which the firm is not registered as an investment advisor. Use of this website is subject to its terms and conditions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.