This observation was originally published at Shell Capital’s ASYMMETRY® Observations.

Markets aren’t driven by averages

Most investment frameworks still assume markets are driven by rational actors optimizing long-term averages.

They aren’t.

Markets are driven by how humans perceive gains, losses, and risk in real time—and that perception is systematically distorted under pressure.

This isn’t speculation. It’s formalized in Prospect Theory, the Nobel Prize-winning framework developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky that explains how people actually behave when real money is on the line.

The asymmetry is structural

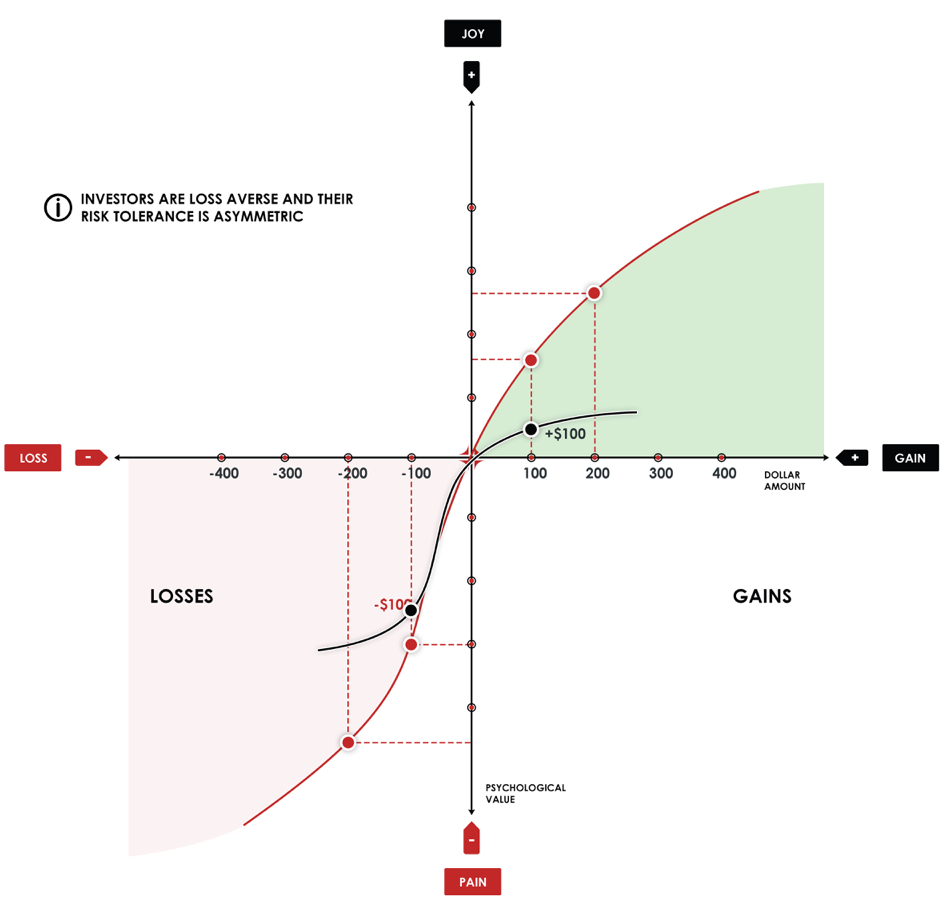

Prospect Theory demonstrates investors are:

- Risk-averse when they’re winning

- Risk-seeking when they’re losing

- Far more sensitive to losses than to equivalent gains

This creates a non-linear value function centered around a reference point—usually “break-even.”

In markets, that behavioral asymmetry shows up as:

- Upside trends that persist longer than expected

- Downside moves that accelerate faster than models assume

- Volatility that clusters rather than distributes smoothly

Averages don’t explain that. Behavior does.

Where wealth gets destroyed

Here’s the problem most investors don’t see coming:

The gap between how portfolios are constructed and how humans actually behave under pressure is where wealth gets destroyed.

Not by market risk. By behavioral risk.

Modern Portfolio Theory assumes you’ll hold through any drawdown. Prospect Theory explains why you won’t—and why trying to force yourself to will likely make things worse.

Loss aversion intensifies as drawdowns deepen. Investors lock in gains too early when winning and hold losses too long trying to “get back to even.” The discipline you think you have evaporates precisely when you need it most.

That’s not a character flaw. It’s human wiring.

From behavior to process

Prospect Theory doesn’t predict what markets will do next. It explains how people react once markets move.

That distinction is critical.

At Shell Capital, we design systems around that reality:

- Downside risk is defined in advance, before loss aversion takes over

- Exits to limit losses are systematic, not emotional

- Upside is allowed to compound when trends persist

- Position sizing reflects asymmetry, not averages

We don’t optimize for theoretical means. We manage the path—how returns are experienced over time.

Because the path is what determines whether you stay invested or tap out.

The practical reality

You can’t behavior-modify your way out of loss aversion. You can only design around it.

Markets aren’t driven by averages—they’re driven by how humans perceive gains, losses, and risk under pressure.

Our systems are built to harness that asymmetry while protecting against the behavioral traps that destroy even well-intended investment plans.

That’s where disciplined risk management begins.

Does your portfolio account for behavioral risk?

At best, portfolios may be stress-tested for market scenarios—2008, COVID, rate shocks.

Almost none are stress-tested for the investor.

One of the many parts of ASYMMETRY® is a behavioral risk diagnostic that maps allocations against asymmetries that emerge under pressure:

- Where loss aversion is likely to override discipline

- Which positions create unintended behavioral exposure

- How your exit strategy (or lack of one) amplifies downside risk

- Whether your position sizing reflects asymmetry or just diversification

If you want to see how your portfolio holds up under behavioral stress, contact us and we’ll send you the framework and walk you through how we apply it to your current holdings.

—Mike Shell President & Chief Investment Officer Shell Capital Management, LLC

You must be logged in to post a comment.